BLOG

Last Rites

He died as I said, “Depart O Christian soul, out of this world.” That’s never before happened to me and it was a parting gift from this lovely, devout man.

People are curious, but are nervous to ask what happens, at least as the Church is concerned, when we die. Families know to call the priest but are often unsure what they are calling us to do. Confession, unction, and Holy Communion (viaticum) constitute the “last rites” of the Church: sacramental strength before our soul is separated from our bodies in death. Very often, at least in my experience, it is not possible to administer all three. In the majority of cases, the dying person is asleep or not communicative, making confession impossible and/or they are unable to eat, making reception of the Holy Communion impossible, leaving only the final anointing with the oil of the infirm (extreme unction).

Ideally the room is to be prepared with candles, holy water, and a crucifix. Again, most of the time such preparations are not possible due to time and other considerations. I keep a violet stole in my car and I used to keep a small crucifix as well. That crucifix is now buried with a man who kept it and held it constantly after I anointed him before his death last year. Yesterday, when I received the call that this servant of God was declining faster than anticipated, I took a crucifix down off the wall, grabbed the oil, cotta, and stole and quickly went to him.

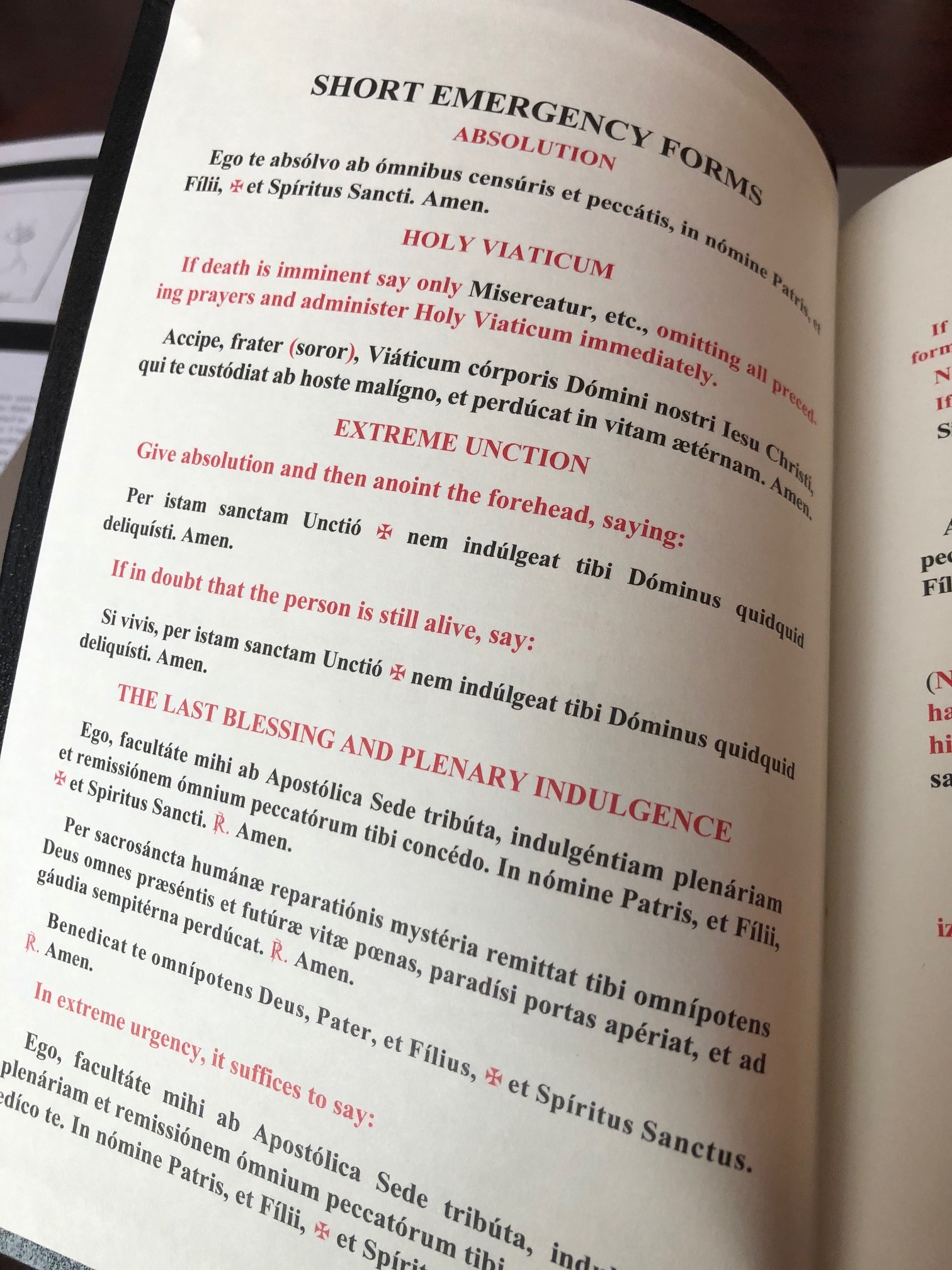

As there is no liturgy called “Last Rites,” the priest must make decisions. The 1979 Book of Common Prayer has liturgies for Reconciliation of a Penitent (confession), Ministration to the Sick (anointing), and Communion Under Special Circumstances (viaticum). A similar arrangement is found in the traditional Roman Ritual. While the 1979 Book of Common Prayer has traditional prayers for the dying (taken from the 1928 Book of Common Prayer, which I should add, also includes absolution), the prayer for anointing in the face of death is wanting. The prescribed words that accompany anointing do not mention the forgiveness of sins but rather state that the person is anointed with oil in the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The optional prayer that follows is wonderful in cases where there is hope for recovery, but not necessarily in the face of impending death. While the line “restore you to wholeness and strength” certainly implies spiritual wholeness and strength, in the case of a dying person I prefer the traditional formula for anointing, “By this holy anointing may the Lord forgive you all the evil you have done." [Of note, the Church of England removed “restore to wholeness and strength” in Common Worship’s Ministry with the Dying, a prudent move.]

The translator’s preface to the 1964 Roman Ritual acknowledges that the rites assume ideal circumstances and while acknowledging that ideal circumstances are often just ‘ideal,’ the preface chastises priests for not doing their part in keeping the fullness of the rite. I think there is real merit to the knuckle slap. It’s not too much effort to put on the cassock, cotta, and violet stole and it’s not too much effort to bring a crucifix, even in situations requiring immediate attention.

In yesterday’s case, as his breathing was very shallow, I knew I didn’t have time for the full traditional rite but I did place my wall crucifix on his chest, put on cotta and stole, and immediately anointed him with the traditional words. Confession and Communion were not possible. In placing the crucifix before them, I ask the person to unite their sufferings to that of the Crucified Lord and call on the Name of Jesus in their hearts. This is very likely the context for Julian of Norwich’s Revelations as she gazed upon the crucifix as she received the ministrations of the Church in her illness.

The Litany for the Dying followed the anointing. It is powerful and sobering and it is good for the family to join the petitions. The Litany follows the structure of the Great Litany and concludes with the Agnus Dei, Kyrie, Our Father, and Collect. It was after the collect asking for God’s deliverance from evil that I again touched the forehead of this servant and made the sign of the cross. His breaths had been far apart but his head was warm.

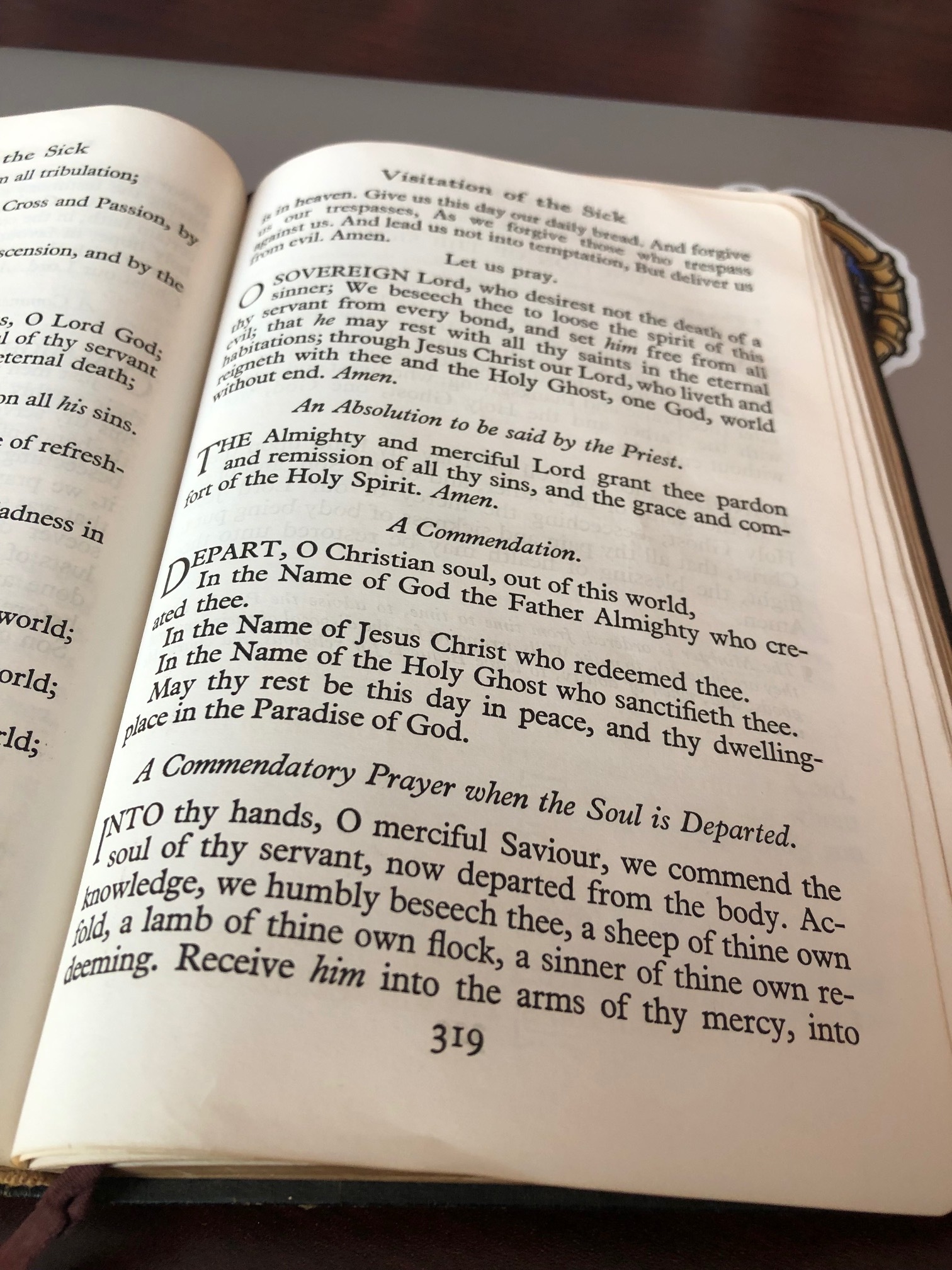

“Depart, O Christian soul, out of this world;

In the Name of God the Father Almighty who created you;

In the Name of Jesus Christ who redeemed you;

In the Name of the Holy Spirit who sanctifies you.

May your rest be this day in peace, and your dwelling place in the Paradise of God.”

I finished with the prayer of commendation and we noticed his color had changed. The breathing had stopped. He obeyed the command and gave up his spirit. It was finished.

As the Church calls is, a happy death.

Dead but not Absent

As unbelievable as it sounds, I have lived nearly a quarter of my life without my mother. Today marks the 9th anniversary of her death.

Grief is a labyrinth with strange contours. I miss my mother and think about her nearly every day, although I don’t think about her as often as I used to. I think about her when my children do something spectacular or stupid, knowing that she would find great pleasure in both. I think of her when something notable happens for me personally. If she were alive, I know she would celebrate with me in a manner that is unique to motherhood.

Mementos of her life and legacy are nearby. Her paddle (she was an elementary school principal) hangs in my office, a tangible sign of tough love. Her nameplate sits on my desk at home and the accolades of her heroism that were given after a shooting at her school are framed in the hallway.

I miss her but I don’t feel absent from her. One of my favorite pictures of us together is from 1994. It was taken at my high school as I was about to leave with my teammates for football camp in the mountains. I didn’t want to go, not because of the two-a-day practices or lodging with five other boys in a tiny room, but because I would be absent from my mama. I was homesick before I left home. If you look at the picture, you can see muscles around my mouth tensed to hold back the quivering of the lips. I was anxious about her absence.

When St Augustine’s mother, Monica, was near death she told her sons, “Bury your mother here.” They were quiet and struggled too, in the face of impending absence, to keep their lip stiff. Augustine’s brother assured Monica that they would take her back to her home country and bury here. This angered Monica. Augustine writes, “She looked in my direction and said, ‘See what he says’, and soon said to both of us ‘Bury my body anywhere you like. Let no anxiety about that disturb you. I have only one request to make of you, that you remember me at the altar of the Lord, wherever you may be.’”

Remembering this request from Monica, I remember my mother at the altar of the Lord, where his Sacramental Presence fills her physical absence. I pray, as Augustine did for his mother, that she has been received by Christ’s mercy and will go from strength to strength in the service of perfect freedom. If she is in Him and I am in Him then, through his love and grace, we are not absent from one another. Rather we are closer now than we were when she was alive. Therefore we do not grieve as those without hope…

While it would be fun for my mother to see my daughter win the Athlete of the Year award or hear about my adventures in London or see the boys grow like weeds, I am not sad. Her gaze is toward something more glorious. She is not absent. How could I be sad about that?

St Augustine wrote: “I dedicate my heart, voice, and writings, that all who read this book may remember at your altar Monica you servant and Patrick her late husband, through whose physical bond you brought me into this life without my knowing how. May they remember with devout affection my parents in this transient light, my kith and kin under you, our Father, in our mother the Catholic Church, and my fellow citizens in the eternal Jerusalem.”

Me too. Please remember, of your charity, Eleanor. A sweet soul and loving mother and friend. Who was, is, and shall be, very much present.

Incensatio super oblata

One of the curious features of the High Mass is the form of censing of the oblata - the offerings of bread and wine that will become the Body and Blood of Our Lord. The priest makes three signs of the cross over the bread and wine and then three circles, two counter-clockwise and one clockwise. Artistic renderings of this act are everywhere and, indeed, serves as the logo of this website.

Atchley in A History of the Use of Incense in Divine Worship shows that the oblata were incensed as early as the 9th century and it was common by the 11th century. The traditional manner of three crosses and circles was prescribed at Cluny.

What I have always wondered was why the three crosses and the three circles. Clearly there is Trinitarian symbolism, but more specifically, why two circles one way and a third the other? In 1905, Passionist Father Arthur Devine wrote the following:

As by the oblations is signified Christ offering Him self willingly to undergo His Passion and Death, so by the incensation of the oblations is signified that voluntary oblation of Christ so sweet and pleasing to His Heavenly Father. The fragrance of the incense, which is emitted from the thurible, designates how pleasant and acceptable was the oblation of Christ to His Eternal Father. In this mystical sense are the words Incensum istud a Te benedictum ascendat ad Te, Domine to be explained and applied. For Christ offered to His Father is the mystical incense of the sweetest odour to God odore suavitatis (with the odour of sweetness). Also the bread and wine offered in the Mass, and after wards changed into the Body and Blood of Christ, will be that same mystical incense of the sweetest odour to God the Father. To this mystical signification the ceremonies of the incensation seemed to be directed. For, in the first place, when the priest incenses the oblations he makes three crosses over them with the fuming thurible, by which is signified that Christ offered, on the Cross, to His Father three things most pleasing and acceptable namely, the Person of Jesus Christ, His holy Soul, and most pure Body. Then with the thurible the celebrant makes three circular swings around the oblations, and this he does in honour of the Holy Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, and to signify that this pleasing and acceptable sacrifice can only be offered to the Holy Trinity or to God alone. By the circular swings is signified the eternity of the Divine Persons. Two of these are made in the same direction and one in the adverse direction, which is interpreted as signifying the Eternal Father as proceeding from no other, the Eternal Son as proceeding from the Father by generation, and the Holy Ghost as proceeding from the Father and the Son, not by generation, or formal likeness by virtue of His procession, but by eternal spiration and love. The aforesaid circles are made around the oblations to signify that the Father and the Holy Ghost are present with the Son in the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist by circumincession, or the inseparable in dwelling of the Persons of the Trinity in each other.

So - the first swing is for God the Father, who proceeds from no one. The second swing is for God the Son, who proceeds by generation (not creation). The third is the Holy Ghost who proceeds not in generation as in the Son, but by spiration as the love between the Father and the Son.